What Is a Module?

Modules should be devices with clear-cut functionality. That is to say, they should have a single, well-defined purpose or a set of closely related functions, rather than an eclectic mix of capabilities onboard. This requirement is designed to reduce complexity, cost, and power consumption and maximize reusability in hardware and software.

One of the main goals of the Tessel platform is “connected hardware as easy as npm install.” If you need an accelerometer, Bluetooth Low Energy connection, SIM card capability, or any of the other first-party or USB modules available, you can literally plug, npm install, and play.

There is also a growing library of community-contributed third-party modules: npm libraries paired with some simple wiring instructions, built for specific pieces of hardware.

But what if your project needs functionality that can’t be provided by one of the existing first- or third-party modules? You make your own, of course.

This guide will walk you through the basics of creating your own Tessel module using our new proto-module boards.

A Quick Note of Encouragement

Making your own module might seem like an overwhelming task best left to those who know things like Ohm’s Law, how to solder, and why licking a 9V doesn’t feel very good. But while having some electronics knowledge doesn’t hurt, it’s not a hard and fast prerequisite. If you know how to program, you are smart enough to figure out the basic concepts and make awesome things happen. Just trust us and read on.

Module Design Basics

Before you venture into the world of custom module creation, we need to cover some basics that will help guide you along the way.

Every module created for the Tessel involves 5 parts:

- Power

- Communication

- Software

- Documentation

- Sharing

If you understand how each of these fit into the module creation process, you will be well on your way to creating your own custom module. Let’s start with power.

Power

When dealing with anything in electronics, whether it be sensors, displays, buttons, or servos, you have to provide power. Everything needs a power source, and Tessel modules are no exception. In its simplest form, you can think of a power source as two connections; a positive voltage and a ground connection. These connections are provided on each Tessel port.

The main Tessel board can be powered several ways, but regardless of how you provide power to the main board it ultimately turns that source into 3.3V. That’s the native “voltage language” of the Tessel. It likes to speak 3.3V to everything if possible.

One of the nice things about the proto-module is that the 3.3V and ground connections are exposed as two rails that run along each side of the module as seen below. This allows you to easily power your module components.

Proto-module power rails

Special Considerations

If all of the components on your custom module operate at 3.3V, then your power design is extremely simple. You just use the 3.3V and ground rails and connect your components accordingly (the custom screen module below is a good example). Sometimes, however, you may encounter a situation where 3.3V is not what you need, like in the case of the servo module.

Many servos like to operate at 5V. That’s their native “voltage language” and so the 3.3V provided by the Tessel isn’t ideal and, in many cases, just won’t work. Servos can also draw a lot of current, which may overwhelm the Tessel’s power supply. To solve this problem, you’ll notice that the servo module has a DC barrel jack on it that allows you to plug in a 5V adapter to provide sufficient power to the connected servos.

DC Barrel Jack on the Servo Module

From the servo module schematic, we can see that communication is accomplished with the normal I2C lines, which operate at 3.3V, but servo power is provided via schematic component J2, which is the barrel jack.

This guide isn’t meant to be a comprehensive power reference, but we just want to point out that if you have any components on your custom module that work outside of the 3.3V realm, you will need to design for it. To simplify your module design, we recommend using 3.3V components where possible.

The Power Warnings

Here are some items to remember when working with power in electronics.

- ALWAYS unplug your Tessel and any external power before making or altering connections.

- Don’t mix voltages unless you know what you’re doing. For example, if you put 5V on any of the module pins, you can ruin your Tessel.

- Never connect the positive voltage directly to ground. This is called a short circuit and can ruin components and your day.

- Always exercise caution and verify that you have hooked everything up correctly before plugging in your Tessel.

Communication

Once you have decided how you are going to power your custom module, it’s time to decide how the main Tessel board will talk to it.

In the world of web communication, there are standards like HTTP, HTTPS, and FTP that allow different systems to talk to each other in well-defined ways. The same concept exists in the hardware world and the Tessel supports four standard communication protocols for talking to modules.

- GPIO

- SPI

- I2C

- UART

Because the Tessel does most of the heavy lifting for all of these, you don’t need to be an expert to use them in your custom module. However, if you’d like to learn a little more, we’ve provided a simple overview of each.

So Which Communication Protocol Should I Use?

Knowing that there are four communication options available to you, which should you use for your custom module? The good news is that this will usually be decided for you based on the type of module you are creating. For example, most PIR sensor modules will set a pin high when motion is detected, which can be read with a simple digital input (GPIO). The same applies to sensors. For example, the Si7020 temperature and humidity sensor on the Climate Module communicates via the I2C protocol. Usually sensors will only support one protocol– so the decision is easy, you use that one.

You will find some modules that support both SPI and I2C, and either will work just fine with the Tessel. As a general rule of thumb, we recommend you favor the SPI protocol in these scenarios as it eliminates the risk of I2C address collisions with other connected I2C modules.

Software

Once you have the power and communication all worked out and connected, it’s time to start writing JavaScript to talk to your module. This is where the open-source nature of the Tessel really comes in handy. We’ve already used all of the possible communication protocols in our modules and the code is free to look at and copy.

Design an API for working with your module so that it’s easy for others to integrate into their projects. As a general rule, top priority is intuitive interaction. Second priority is exposing as many features as you can. You can find a lot of great information about organizing your project and writing an API in Making a Tessel-style Library for Third-Party Hardware.

Documentation and Sharing

Once you have a working module, it’s time to share the good news with everyone so other people can build amazing things with your work. We recommend doing a few things to share it with the community as outlined below. This helps create a consistent feel across all Tessel modules, whether they are official modules or submitted by the community.

Create A Git Repo

Having your code in a git repo and available online makes it easy for others to grab your code and start using it in their projects. To help you get started we’ve created a template repository that you can use as a starting point.

Custom Module Git Repo Template

Document It

You may have just created the world’s most amazing Tessel module, but how is anybody going to know about it or use it? Once you’ve hashed out the API and everything is working, it’s important to document its use so others can easily apply your work to their projects. The best way to do this is to use the README template, which includes things like how to install the module, example usage, and API information.

Publish Your Code on NPM

Once your git repo is ready and you’ve documented your module, this step is really easy and makes your module fit the Tessel motto of “connected hardware as easy as npm install.” If you’ve never published code to NPM before, you can get started with just four lines of code (run in a shell window).

npm set init.author.name "Your Name"

npm set init.author.email "you@example.com"

npm set init.author.url "http://yourblog.com"

npm adduser

This sets up your NPM author info. Now you’re ready to create your package.json file. There is one in the repo template but we suggest creating it by running npm init from within the project directory.

npm init

Edit your package.json file to include a name, version, and description. We also highly recommend adding “tessel” as a keyword so that other Tessel users can easily find your work. Most of the package.json file is self-explanatory and follows the npm package.json standard with the exception of the hardware member.

**hardware** section of package.json

This is a Tessel-specific item that you must add manually and is a list of files and folders in your project that you would like to exclude when code is pushed to your Tessel.

Once your package.json file is complete you’re ready to publish your code. Run the following command from the top level directory of your project.

npm publish ./

Create a Project Page

The Tessel Projects page is a way to share your module directly with the Tessel community. You simply provide a few pieces of information, a picture, and can even use your README.md file from your Git repo as the contents.

Submit Your Module

We’re always looking to add modules to our third-party module list so if you’d like your custom module to be listed at tessel.io/modules then fill out this form and we’d be happy to review it.

Third-Party Module Submission Form

A great example of using this module-creation pattern can be found in Making a Tessel-style Library for Third-Party Hardware.

Your First Custom Module

So now that we’ve described the pattern for making a custom module, let’s walk through creating a very simple module using that pattern. The Tessel has a spare button on the main board, but maybe you’d like to add one as a module. Kelsey did a great writeup on adding a button to the GPIO bank so let’s use her work to take it one step further using a proto-module.

Power

You might not think of a button as needing power, and you’re right, sort of. While the button itself doesn’t need power to function, we can connect our button in such a way that it uses the power connections to create high and low states on a GPIO pin.

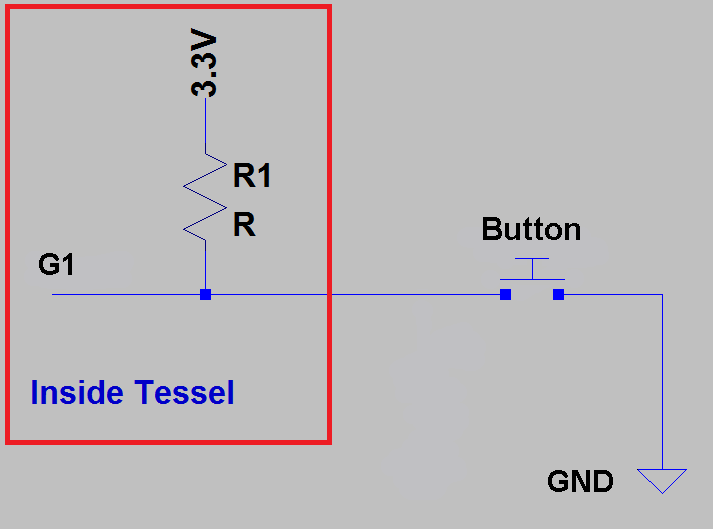

GPIO pins on the Tessel will always read high/truthy with nothing connected, because internally (inside the main Tessel chip), they are pulled up to the 3.3V supply. That’s our positive connection.

The other power connection is ground, which we’ll connect to one side of our button. It doesn’t matter which side, because a button is just a momentary switch that creates and breaks a connection. You can’t hook it up backward. We’ll get to connecting the other side of the button in a minute.

Communication

As mentioned above, normally your communication protocol is determined by your module. In the case of a button, we use a digital GPIO pin because we want to read the state of the button.

Each port on the Tessel has several digital I/O pins that can serve this purpose, and you are free to pick any one you like because it doesn’t matter.

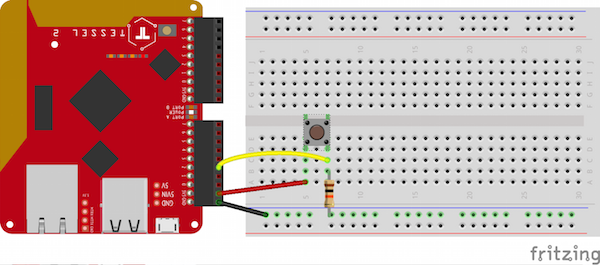

We’re going to choose port A’s pin 1, which is what we will hook up to the other side of the button. When the button is not pressed, our input pin will read high, or true. When we press it, we are making a connection between our GPIO pin and ground, which will cause a low state to be present on the input pin. This is what the design looks like.

Schematic of button connections

Soldered together on a proto-module board.

Don’t let the soldering part scare you. Soldering components like this onto a proto-module is a little harder than learning to use a hot glue gun, but not a lot harder. This tutorial from Sparkfun is a great place to start learning soldering.

Let’s go ahead and plug our module into Port A. Remember to never make connections while your Tessel is powered up. Always unplug it first.

Software

With everything hooked up, it’s time to write some Javascript.

Actually, we’re going to reuse the code from Kelsey and modify it just a bit. Since she followed the style guidelines and shared her work on NPM, we actually don’t have to write the bulk of the code. She’s even provided a Quick Start guide in her documentation, so we’ll use that.

- Install the tessel-gpio-button package. This will allow us to reuse Kelsey’s work.

npm install tessel-gpio-button - Create a file named myButton.js and copy her Quick Start code into it. It should look like this:

// examples/button.js // Count button presses var tessel = require('tessel'); var buttonLib = require('../'); var myButton = buttonLib.use(tessel.port['GPIO'].pin['G3']); var i = 0; myButton.on('ready', function () { myButton.on('press', function () { i++; console.log('Press', i); }); myButton.on('release', function () { i++; console.log('Release', i); }); });

This almost works right out of the box. We just need to make two small adjustments. Do you see them?

First, to include her module we won’t use “require(‘../’).” Instead we’ll include the module directly with require(‘tessel-gpio-button’).

Second, she hooked her button up to the G3 pin on the Tessel 1’s GPIO bank, but we’ve hooked our proto-module up to Port A on Tessel 2 and used pin 1. So all we have to change is the line where myButton is defined. We’ll change it to be:

var myButton = buttonLib.use(tessel.port['A'].pin[1]);

Save your changes and test it out.

tessel run myButton.js

Every time you push your button it should log to the console.

Congratulations! You just created your first custom module for the Tessel.

Documentation and Sharing

We sort of cheated for our first module; Kelsey had already created an NPM package that we could reuse, so there wasn’t really anything to document or share on the software side. There is nothing wrong with that. In fact, the less code you have to write, the better. This is a great example of how taking the time to document and share your work benefits the entire community.

What we can do though is create a project page showing how we took Kelsey’s button to the next level in the form of a plug-in module. We created the physical module. It’s a simple module, but we should document it in case someone else wants a button module like ours.

Custom Screen Module

Now that you have a simple module under your belt, it’s time to level up. To date, the module that people have requested the most is a screen module. Displays are tricky because they come in so many flavors. There are simple 7-segment displays, LCD displays, OLEDs, resistive touchscreens, capacitive touchscreens, and more. This is a great use case for a custom module.

One of the popular screen modules in embedded projects is the Nokia 5110, because of its simple interface and low cost. Let’s see how we’d create a module for it by following the same pattern as before.

For this example we’ll use the Nokia 5110 breakout from Sparkfun, but you could also use the Adafruit version of the screen or just try to snag one on Ebay

Nokia 5110 Graphic LCD

Power

The 5110 has a listed power supply range of 2.7V to 3.3V, which means any voltage in between (inclusive) is sufficient to power the screen. Since the Tessel ports have a 3.3V supply pin we don’t have to do anything special to hook it up. All we need to do is connect the screen VCC, or positive pin, to a 3.3V rail on the proto-module and the GND on the screen to a GND rail.

Because of the screen’s size, we’ll use one of the double-wide proto-modules this time, even though we’ll only use a single port to connect everything.

Double-Wide Proto-Module

Communication

Just like in the button example, the communication protocol for the screen has already been chosen for us. The Nokia 5110 uses a slightly modified version of SPI to communicate with a parent controller, namely the Tessel in our case.

In addition to the normal SPI protocol, the 5110 has an extra pin involved (D/C) that tells the screen whether the data we are sending via SPI is a special command or actual screen data.

The D/C pin is controlled by a simple high or low signal, which is a perfect job for one of the GPIO pins.

The following table shows all of the communication connections available on our screen and how we’ll attach them to the Tessel port.

| Nokia 5110 Pin | Proto-Module Connetion |

|---|---|

| SCE | G1 |

| RST | Connected to 3.3V through 10K resistor |

| D/C | G2 |

| MOSI | MOSI |

| SCLK | SCK |

| LED | Connected to G3 through 330 ohm resistor |

Design Note

The Nokia 5110 has 4 connections that can utilize GPIO pins for functionality. The D/C (data/command) and SCE (chip select) pins have to be used to get data to the screen. That leaves just one GPIO pin on the port with RST and LED left unconnected. You have a few options here.

- Wire RST to 3.3V through a 10K resistor which prevents you from resetting the screen in code. This allows you to control the backlight with the free GPIO pin.

- Wire LED to 3.3V through a 330 ohm resistor (to limit current) which will permanently turn on the backlight. This leaves a GPIO free that can be used to reset the screen via Javascript.

- Since we’re using the double-wide, you could use a GPIO pin from the adjacent port and have use of both LED and RST

- Connect SCE (chip select) to ground, which frees up a GPIO so you can control both LED and RST. Holding the chip select low, however, makes it so that no other SPI device (including other Tessel modules that use SPI e.g., the Camera module) can be connected to the Tessel on any other port.

We decided to go with option 1 because there isn’t really a need to reset the screen in most cases and it allows control of the backlight with a GPIO pin. This is another great thing about custom modules. You can design it however you want to fit your project needs.

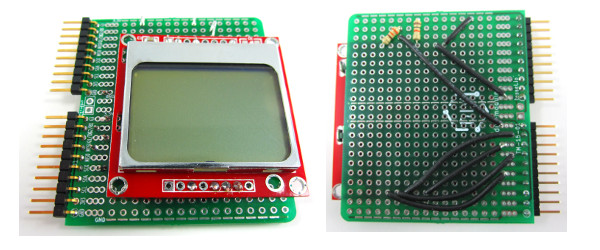

We hooked everything up using the Graphic LCD Hookup Guide. We recommend testing everything with a breadboard before you solder everything in place, just to make sure it works the way you expect it to.

Here is what the module looks like soldered to the double-wide proto-module.

Nokia 5110 soldered to a large proto-module board

Software

With the screen hooked up, it’s time to start writing code. We’ll follow the pattern found in the Git Repo Template and start by creating a directory called tessel-nokia5110 and cd into that directory. Next, we’ll use t2 init to create index.js which is where we’ll write our API using the example index.js template as a guide.

Because this screen is so popular, there are lots of code examples and libraries online for interacting with it. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel; we just want to control the screen with JavaScript.

We took a simple Arduino library for this screen and ported it to JavaScript. Our API is very simple and exposes just one event and a few methods.

Event

Nokia5110.on(‘ready’, callback(error, screen)) – Emitted when the screen object is first initialized

Methods

Nokia5110.gotoXY(x,y,[callback(error)]) – Sets the active cursor location to (x,y)

Nokia5110.character(char, [callback(error)]) – Writes a single character to the display

Nokia5110.string(data, [callback(error)]) – Writes a string to the display

Nokia5110.bitmap(bitmapData, [callback(error)]) – Draws a monochrome bitmap from bitmapData

Nokia5110.clear([callback(error)]) – Clears the display

Nokia5110.setBacklight(state) – Turns the backlight on if state is truthy, off otherwise

Documentation

Now that the module is connected up and the software is working, it’s time to document its use.

We can’t stress enough how important this is, and it really only takes a few minutes once you’ve defined everything. Just think of all the times you’ve needed a piece of code and found a beautifully documented example that had you up and running in minutes. Share that love with others when you create your own modules, no matter how trivial you think they are.

In our case, we’ll take the template README.md file and add some notes for getting started as well as document our API.

We’ll also create an examples folder to show how the module can be used.

Sharing

Now it’s time to share our new creation with the world by:

- Creating a git repo and pushing the code online

- Publishing the module to NPM

- Creating a project page for it

- Submitting it to the third-party module list

Finished screen module

Resource List

To help you get started creating your own custom modules, here is a list of the resources we used to put this tutorial together.

Power

Communication

Software

- Making a Tessel-style Library for Third-Party Hardware

- Tessel Hardware API

- All first-party module code on Github